But I do want to talk about the following 7 points of my aphasia that were especially hard on me.

1. The off switch.

Like so many strokes, my stroke had no warning. It came on during the early morning and progressed fast. By the time I had alerted my husband that something was wrong, I had lost the power of speech. But the worst thing about aphasia is not “being unable to speak” but being unable to speak suddenly. Aphasia is like an on/off switch. One day I could laugh and talk, the next moment I couldn’t say a single word. This sudden loss was far worse than not being able to walk. What was so quickly taken away from me became a torturous job of small steps to regain my speech.

2. Stuck on a word.

One of the ironies of aphasia is in addition of not being able to say the word you want, is being able to say a word you don’t want over and over. This is called to perseverate. In my case, I would get stuck when I was practicing saying a list of words that my therapist gave. You have no idea how frustrating it is when a word comes out unbidden again and again from your mouth when you are trying to say something else. In extreme cases, a person can only say one or two words over and over again. Several people in my stroke group have had perseveration like this and my heart goes out to them.

3. Speaking of numbers.

People who have aphasia problems often also have problems with another form of language – the language of numbers. The first time I noticed I was having trouble with numbers was when a nurse asked me how tall I was. I tried to tell her but I kept getting it all wrong. Even now, I have trouble working with and remembering numbers – even my phone number and my address – and I am hopeless at figuring out a tip at a restaurant. More embarrassing, when I hold up my fingers to show a number, I usually get it wrong until I look at them.

4. Making a choice.

It’s well known that people with aphasia often say yes when they mean no, and the other way around. This yes/no confusion usually resolves itself quickly, as it did with me. But in my case, I was left with several other similar problems. For example, I still have an issue with he/she and him/her. I know the difference between them; I know which one is correct; but I have to say them both out loud and then pick the right one by ear. I also still have to make the rounds with saying would/should/was/were. Sometimes I have cycle around again until I settle on the right one.

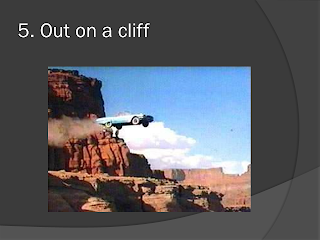

5. Out on a cliff.

My aphasia has gotten a lot better over the years but it still rears its ugly head, oftentimes in mid-sentence. It’s as if I am driving down a highway, the words are flowing by, and then BAM, I screech to a halt, looking out into a hazy distance over an edge, not being able to go forward, to finish my sentence or express my thought that is still so clear in my mind. This makes me repeat the start of the sentence over and over until the ending comes back to me.

6. Too small to be noticed.

When there is very little content in a word, people with my kind of aphasia have a hard time paying attention to it, especially when the words are small. I found that I was omitting these so-called “function” words in writing – like in emails. Helping verbs were especially hard for me to notice.

For example, if you read this as “A bird in the bush,” you have skipped over a function word too – the second THE. It really says “A bird in the the bush.” Many people have trouble seeing the second THE – even when it’s pointed out to them. This classic illusion hasn’t really anything to do with aphasia, but it gives you some idea of what it’s like to not see (and therefore to not say) small words. These small words are important to good communication because they make up the grammar in our speech, but are too small to be noticed for a person with aphasia.

Take the question “Do you take me for a fool?” The only content words there are “you, me, fool.” All the rest are small function words (do, take, for, a), and they are lost to the aphasic mind, either in writing (as in my case), or speaking (as in telegraphic speech), or even in understanding.

7. At a loss ... for idioms.

All of a sudden, I was at a loss with coming up with the expressions “all of a sudden” or “at a loss” or “come up with” or any of the hundreds of idioms that I once used so freely. I think I couldn’t wrap my mind around them because the words of these common sayings are basically content-less. This isn’t the case with all sayings. To “turn over in one’s grave” has plenty of concrete images to visualize! My therapists counseled me to use a different word or phrase. I couldn’t really explain to them that saying it plainly was tantamount to not saying it at all, that my aphasia took away the way of speaking that I so loved.

These 7 things – and much more – make up the world of a person with aphasia. In time, my aphasia has largely gone away. Some people are not so lucky. But all people with aphasia – no matter how severe – have to constantly strive to make themselves heard, to communicate, and to reach out to other people. And you can do your part by being there to listen to us.

Thank you.